Apple + Recommended + Security & Privacy

The Evolution of macOS Security and Privacy Features

Posted on

by

Joshua Long

The ever-changing threat landscape has necessitated the evolution of computer operating systems, and macOS is no exception. It has become increasingly clear that Macs were not simply “safe” right out of the box. Mac malware and exploits are really out there in the wild, and not just some mythical menace. Mac users have also been targets of fraud, identity theft, and espionage campaigns, just like Windows users.

To help protect its customers and combat some of these threats, Apple has added many security and privacy-enhancing features to macOS over the past decade. With each major revision, along with incremental security updates, Apple has continued to improve the Mac’s baseline security.

Following is a timeline of security improvements that Apple has made starting with the release of Mac OS X 10.4 Tiger and continuing through subsequent versions of the Mac operating system, up to and including OS X 10.11 El Capitan.

Mac OS X 10.4 Tiger (released in April 2005)

After 2004 saw the introduction of more than one OS X Trojan horse, including the much-publicized Renepo/Opener, Apple needed to do something to beef up Mac security and help users feel safe again.

In Mac OS X 10.4 Tiger, Apple included a new feature called Download Validation, an early attempt at helping users identify when they were about to download something that could potentially be harmful, including applications, scripts, and webarchives (complete pages saved with Safari). The feature wasn’t foolproof, however; it treated pictures, video and audio files, and PDFs as “safe,” meaning that attacks such as PDF exploits could easily be perpetrated in spite of Download Validation.

Apple added access control lists (ACLs) to Tiger as a supplement to traditional UNIX file permissions. You can read more about OS X ACLs at Ars Technica and TechRepublic.

Tiger also added an “extended attributes” metadata feature to the file system, which paved the way for Leopard’s quarantine bit mentioned below.

Mac OS X 10.5 Leopard (released in October 2007)

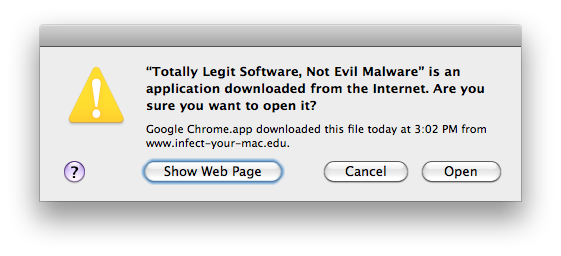

In Mac OS X 10.5 Leopard, Apple added a feature known as File Quarantine, which consisted of adding an extended attribute flag (com.apple.quarantine) to files downloaded from the Web (via Apple apps such as Safari, or via third-party apps that chose to implement the feature). When certain types of downloaded files were opened for the first time, users were presented with a warning dialog box notifying them of the site from which it was downloaded as well as the date and time of the download.

Image credit: Joshua Long

The ability for developers to digitally sign their code was also introduced in Leopard. Since then, this feature has received significant improvements, and it’s important to note that code signing was a prerequisite for Apple’s eventual addition of “Gatekeeper” functionality to Mountain Lion as well as the final version of Lion (read on for more about Gatekeeper).

Leopard was the second and final major release of Mac OS X to officially support both PowerPC and Intel processors. Leopard’s PowerPC version (which ran on G5 and higher-end G4 processors) was the first version of Mac OS X to not include the “Classic environment.” From the very first version of Mac OS X all the way through Tiger, Classic had enabled software written for Mac OS 9 or earlier to run alongside Mac OS X applications. A side effect of Classic’s demise was that most malware developed prior to OS X could not infect upgraded Macs.

Leopard was the second and final major release of Mac OS X to officially support both PowerPC and Intel processors. Leopard’s PowerPC version (which ran on G5 and higher-end G4 processors) was the first version of Mac OS X to not include the “Classic environment.” From the very first version of Mac OS X all the way through Tiger, Classic had enabled software written for Mac OS 9 or earlier to run alongside Mac OS X applications. A side effect of Classic’s demise was that most malware developed prior to OS X could not infect upgraded Macs.

Mac OS X 10.6 Snow Leopard (released in August 2009)

The most well-known security enhancement in Mac OS X 10.6 Snow Leopard is Apple’s introduction of XProtect, which Apple somewhat confusingly called the “safe downloads list,” even though it was originally designed to block certain known malware from being downloaded.

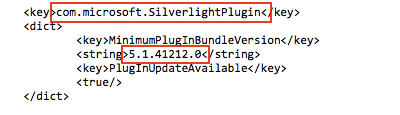

In September 2012, Apple enhanced the XProtect functionality to also block outdated versions of two common browser plug-ins, Adobe Flash Player and Oracle Java, which were often exploited by malicious or infected Web sites and advertisements, and in January 2016 Apple began blocking outdated versions of Microsoft Silverlight.

In September 2012, Apple enhanced the XProtect functionality to also block outdated versions of two common browser plug-ins, Adobe Flash Player and Oracle Java, which were often exploited by malicious or infected Web sites and advertisements, and in January 2016 Apple began blocking outdated versions of Microsoft Silverlight.

As of February 2016, Apple continues to update the XProtect signatures for Snow Leopard, even though Apple has long since stopped patching the core Snow Leopard operating system along with its versions of Safari, iTunes, and other components. Anyone still using Snow Leopard would be wise to upgrade to the latest version of OS X if their Mac can handle it (see “What to Do if Your Mac Can’t Run OS X Yosemite“; stay tuned for an El Capitan update, coming soon).

As nice as it is to have a “bad download” blocker built into OS X, it is important to note that XProtect’s static signatures are typically only updated once or twice a month, and only when there’s a particularly wide outbreak of Mac malware or a high prevalence of Flash or Java exploits that may affect Mac users. As such, XProtect is extremely unlikely to protect against exploits, new malware families, strategically altered variants of existing malware, or even whole categories of malware such as Word and Excel macro viruses (yep, those are still around and are capable of infecting Macs).

Furthermore, XProtect does not actively scan your computer for threats, and it cannot do anything to help you if your Mac is already infected. While better than nothing, XProtect can only be reasonably considered a supplement to, and not by any means a replacement for, an actual Mac anti-virus product.

Apple itself admits this; the company stated to Macworld in 2009, “The feature isn’t intended to replace or supplant antivirus software, but affords a measure of protection against the handful of known Trojan horse applications that exist for the Mac today.” Although Apple tried to downplay the prevalence of Mac malware at the time, a significant number of new threats targeting the Mac have been in the wild in the intervening years; see The Safe Mac’s list of top threats (covering the 1990s through November 2014) and our 10 Years of Mac Malware: How OS X Threats Have Evolved [Infographic] (covering 2006 through the end of 2015).

It cannot be emphasized enough that using a Mac without antivirus software in today’s day and age is quite a bit like driving on the highway without a seatbelt; you might get lucky and never get hit, but it would be rather reckless to take that risk. We urge you to check out Intego’s Mac security products and decide which is best for you.

OS X 10.7 Lion (released in July 2011)

OS X 10.7 Lion introduced FileVault 2, offering full-disk encryption. This was an improvement upon the FileVault feature of previous versions of OS X which only had the ability to encrypt individual user accounts. FileVault 2’s whole-disk encryption is more secure, in part because virtual memory swap files, system logs, and other potential sources of data leakage are encrypted. We’ve previously covered FileVault on The Mac Security Blog; search for articles tagged with FileVault and click “load more posts” to find even more articles.

OS X 10.7 Lion introduced FileVault 2, offering full-disk encryption. This was an improvement upon the FileVault feature of previous versions of OS X which only had the ability to encrypt individual user accounts. FileVault 2’s whole-disk encryption is more secure, in part because virtual memory swap files, system logs, and other potential sources of data leakage are encrypted. We’ve previously covered FileVault on The Mac Security Blog; search for articles tagged with FileVault and click “load more posts” to find even more articles.

Apple also made security enhancements to address space layout randomization (ASLR), making programs more attack-resistant by using memory in less predictable ways.

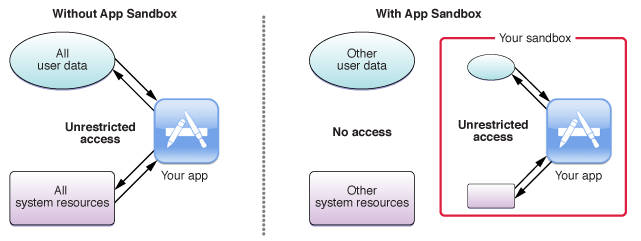

App Sandbox was introduced in Lion, designed to suppress potential damage caused by third-party applications or the exploitation thereof, and to reduce a compromised or misbehaving app’s ability to steal or damage a user’s data.

Image credit: Apple

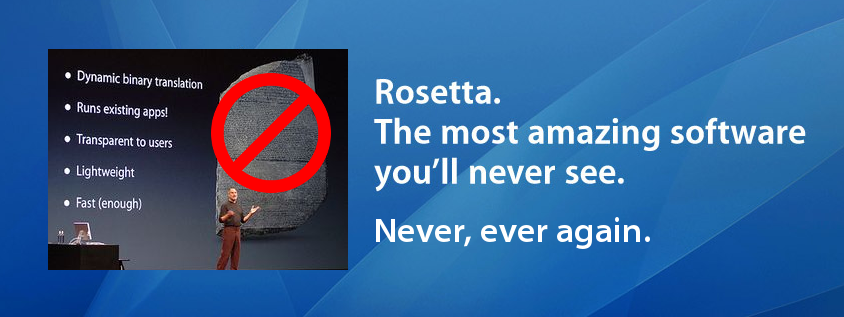

Lion removed the “Rosetta” feature that was included with Intel versions of Tiger, Leopard, and Snow Leopard. Rosetta had given users of Intel Macs the ability to run PowerPC-native software (i.e. apps designed to run on G3, G4, and G5 processors). The removal of this feature had a positive side effect for OS X security, in that older PowerPC-native OS X malware could no longer run.

Image credits: Apple, The Next Web; inspired by OS X Daily.

Apple also added the new Gatekeeper feature from OS X 10.8 to the final version of Lion, 10.7.5.

OS X 10.8 Mountain Lion (released in July 2012)

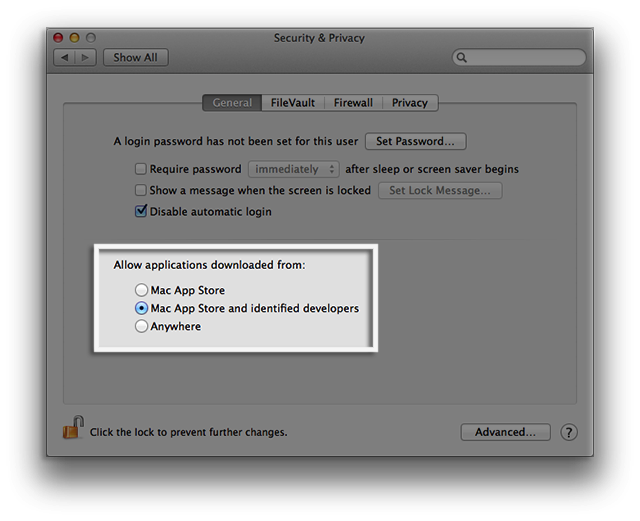

The most notable security improvement in OS X 10.8 Mountain Lion was Gatekeeper, a feature designed to help prevent malware and sketchy programs downloaded from the Internet from running. It added a new set of options in the Security & Privacy section of System Preferences, where the user could choose to allow applications downloaded from: the Mac App Store only, the Mac App Store and “identified developers” (meaning developers registered with Apple), or anywhere.

The most notable security improvement in OS X 10.8 Mountain Lion was Gatekeeper, a feature designed to help prevent malware and sketchy programs downloaded from the Internet from running. It added a new set of options in the Security & Privacy section of System Preferences, where the user could choose to allow applications downloaded from: the Mac App Store only, the Mac App Store and “identified developers” (meaning developers registered with Apple), or anywhere.

Image credit: Apple

Does Gatekeeper really help? Well, it certainly adds an additional hurdle that makes it a bit more difficult to infect a Mac with drive-by downloads or other deceptive tactics. However, sites hosting malware can trick victims into using a workaround to open apps from unregistered developers. It’s as simple as asking the victim to, after the download completes, control-click on the app and select Open, which brings up a dialog box with an option to open the program even if it’s from an unidentified developer.

Worse yet, malware authors can (and sometimes do) register for Apple developer accounts, or hijack legitimate developers’ accounts, to become an “identified developer,” so they can bypass Gatekeeper’s default settings. Here’s a recent example of Mac malware signed by Apple’s Root Certificate Authority.

And, of course, occasionally Apple has accepted apps into one of its App Stores that turned out to have some questionable or even malicious functionality.

Nevertheless, choosing a stricter default setting for Gatekeeper can be helpful for casual users who rarely if ever download new software.

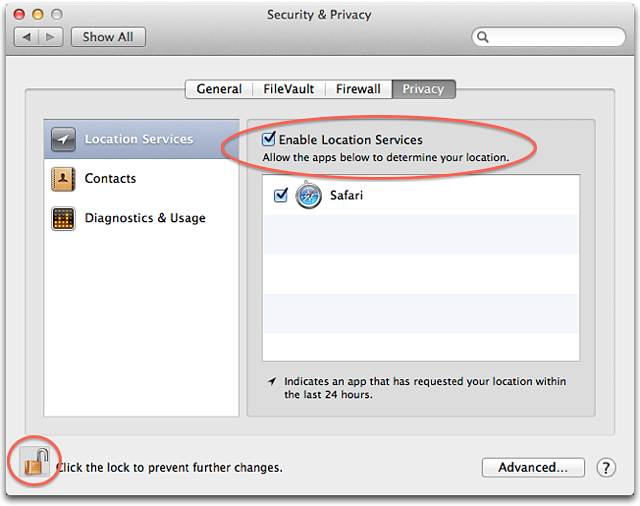

Aside from Gatekeeper, Mountain Lion also introduced a feature called Location Services that could be enabled to allow applications to more accurately determine one’s geographic location. Along with this feature came a new privacy option in System Preferences, allowing users to see which apps had requested their location within the last 24 hours, or to disable Location Services on a per-app basis.

Image credit: Apple

Apple also made improvements to its application sandboxing functionality in Mountain Lion. For more information, you can watch a WWDC 2012 video (requires Safari) covering Mountain Lion’s new App Sandbox features.

Apple also made improvements to its application sandboxing functionality in Mountain Lion. For more information, you can watch a WWDC 2012 video (requires Safari) covering Mountain Lion’s new App Sandbox features.

As noted previously in the Snow Leopard section, a couple months after Mountain Lion’s initial release, Apple upgraded XProtect’s functionality to start blocking outdated versions of the Flash Player and Java plug-ins, and this feature was retrofitted into Lion and Snow Leopard’s versions of XProtect as well.

OS X 10.9 Mavericks (released in October 2013)

In OS X 10.9 Mavericks, Apple introduced iCloud Keychain, a feature designed to synchronize usernames, passwords, credit card information, and Wi-Fi networks between Mac and iOS devices. This is essentially Apple’s answer to the growing popularity of password managers; Apple would prefer to handle this for you (and, of course, keep you locked into the Apple ecosystem by doing so). Apple does use industry-standard security measures to protect iCloud Keychain data, but the paranoid among us tend to be at least a bit concerned about so many users’ passwords being stored in one place in the cloud; it makes Apple’s iCloud servers a potentially huge target for determined groups of attackers with vast resources.

In OS X 10.9 Mavericks, Apple introduced iCloud Keychain, a feature designed to synchronize usernames, passwords, credit card information, and Wi-Fi networks between Mac and iOS devices. This is essentially Apple’s answer to the growing popularity of password managers; Apple would prefer to handle this for you (and, of course, keep you locked into the Apple ecosystem by doing so). Apple does use industry-standard security measures to protect iCloud Keychain data, but the paranoid among us tend to be at least a bit concerned about so many users’ passwords being stored in one place in the cloud; it makes Apple’s iCloud servers a potentially huge target for determined groups of attackers with vast resources.

In Mavericks, Apple began to require code signing for kexts (PDF link; “kext” is short for kernel extension) installed in /Library/Extensions as a means of preventing unregistered developers from making persistent modifications to the operating system’s kernel.

In Mavericks, Apple began to require code signing for kexts (PDF link; “kext” is short for kernel extension) installed in /Library/Extensions as a means of preventing unregistered developers from making persistent modifications to the operating system’s kernel.

Apple also improved file sharing security in Mavericks by adding support for SMB2 (Server Message Block 2), which became the new default Mac file sharing protocol rather than AFP (Apple Filing Protocol), and also became the default Windows file sharing protocol in Vista. For further reading, see the Mavericks Core Technology Overview (PDF) and Microsoft’s overview of the protocol.

OS X 10.10 Yosemite (released in October 2014)

Yosemite introduced a new feature of Apple Mail called Mail Drop, which allowed users to send “attachments” of up to five gigabytes without actually attaching a file to the e-mail. A security and privacy advantage of Mail Drop is that attachments expire thirty days from when the e-mail is sent; after that they can no longer be downloaded. Thus if the recipient’s e-mail account gets compromised at some point more than thirty days in the future, an attacker won’t be able to retrieve past “attachments” you sent them, whereas with traditional attachments they would be able to retrieve them. Unfortunately, Mail Drop is currently limited to (what Apple deems) attachments “too large to send in email,” so not everyone can take advantage of this feature for any attachment.

Yosemite introduced a new feature of Apple Mail called Mail Drop, which allowed users to send “attachments” of up to five gigabytes without actually attaching a file to the e-mail. A security and privacy advantage of Mail Drop is that attachments expire thirty days from when the e-mail is sent; after that they can no longer be downloaded. Thus if the recipient’s e-mail account gets compromised at some point more than thirty days in the future, an attacker won’t be able to retrieve past “attachments” you sent them, whereas with traditional attachments they would be able to retrieve them. Unfortunately, Mail Drop is currently limited to (what Apple deems) attachments “too large to send in email,” so not everyone can take advantage of this feature for any attachment.

The version of Safari included with Yosemite defaulted to showing only the domain in the address bar, rather than the entire URL. Some argued that this increased security for the average user, because it prevented attackers from hiding behind convoluted URLs such as paypal.com.login.edu (which could be mistaken for a page on PayPal’s site; “login.edu” is the actual site in this example). Users can still see the full URL by clicking in the address bar. Another change to Yosemite’s Safari was that, for the first time, Apple introduced per-window Private Browsing, making the feature a bit more convenient.

Apple introduced the Swift programming language alongside Yosemite, which has a number of security advantages. Although Apple does not force developers to use Swift (at least not yet), Apple has given developers an easier way to write software that is inherently more secure.

Apple introduced the Swift programming language alongside Yosemite, which has a number of security advantages. Although Apple does not force developers to use Swift (at least not yet), Apple has given developers an easier way to write software that is inherently more secure.

OS X 10.11 El Capitan (released in September 2015)

The most important new security feature in OS X 10.11 El Capitan is Apple’s introduction of System Integrity Protection, a feature designed to prevent a privileged user or software running as root from modifying or tampering with certain important system files and folders, as well as every running process. This can prevent a user from accidentally damaging the OS, and it’s also designed to help prevent malware from injecting itself at a deeper level (PDF) where it can be more difficult to remove. System Integrity Protection is enabled by default, but Apple currently allows users to disable it after booting to the Recovery partition.

Apple also introduced App Transport Security (ATS), which encourages developers to use HTTPS and more specifically TLS 1.2 with forward secrecy (the latest successor to SSL), when their apps initiate Web requests to back-end servers (for example, to send or receive user data from the “cloud”). Apps created for El Capitan and iOS 9 have this feature enabled by default, but for now Apple allows developers to easily opt out and continue making connections using weaker encryption (e.g. SSL) or without encryption (HTTP).

Additionally, Apple updated XProtect in January 2016 to block vulnerable versions of Microsoft’s Silverlight browser plug-in (which Microsoft is gradually phasing out). This XProtect update was retroactive all the way back to Snow Leopard.

Additionally, Apple updated XProtect in January 2016 to block vulnerable versions of Microsoft’s Silverlight browser plug-in (which Microsoft is gradually phasing out). This XProtect update was retroactive all the way back to Snow Leopard.

What’s Next?

Each new version of macOS released over the past decade has included additional features, enhancements, and modifications that have improved the baseline security of the operating system. It is commendable that Apple continues to make efforts to increase macOS security in new ways with each release. Of course, as is expected of major software companies, Apple also releases security updates to remediate vulnerabilities discovered in the current (and often one or two previous) versions of the OS.

Do all of these security features actually help make Macs more secure? As mentioned to some degree above, many security enhancements can be worked around by a determined attacker (for further reading, see our previous article on the topic). Even with all that Apple has done and continues to do to keep Mac users safe, it’s critical for users to stay aware of the various types of attacks they may face on a daily basis, and to continually learn how to avoid falling victim to them. We encourage you to subscribe to The Mac Security Blog via the e-mail sign-up form in the sidebar, and to follow us on Facebook and Twitter, to stay abreast of Mac security threats.

Whether Mac users want to admit it or not, in this day and age, it’s necessary to take additional precautions to protect oneself from common threats; we cannot rely on Apple alone to protect us. Naturally, we recommend that users take a look at Intego’s offerings that can help keep you safer and more secure at home or at work. We’ve also previously covered a few third-party physical security products and password managers (these are not endorsements, but can give you a good idea of what else is out there).

Related: